BIENNALE MATTER OF ART

Group exhibition curated by by Katalin Erdődi and Aleksei Borisionok

Organized by Tranzit.cz, National Galery Prague – Trade Fair Palace

June – September 2024

RURAL CHANGE AS SOCIAL CHANGE AND THE LEGACIES AND FUTURES OF WORKERS’ MOVEMENTS

The two curators, Katalin Erdődi and Aleksei Borisionok, graft their interests in rural change as social change and the legacies and futures of workers’ movements in order to focus on forgotten stories of social unrest and underrepresented micro-histories of sociopolitical transformation in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond. Bringing together diverse artistic contributions and discursive interventions, the curators look for the resonances between historical struggles and the contemporary moment. Working through the notion of grafting – taken from agriculture and medicine – Matter of Art creates connections between social movements across the changing contexts of the rural and the urban, attending to how the notion of work and the worker finds new meanings. The Biennale Matter of Art marks the first ever collaboration between Erdődi and Borisionok, who are both based in Vienna.

“The unfolding global crisis spans from the extractive work of bodies and algorithms to the exhaustion of living conditions on our planet. Therefore, we ask what can be retrieved from the history of workers’ movements. Labor unrest, both failed and successful, can illuminate the present moment and possible futures of solidarity, political organizing, and justice,” says curator and writer Aleksei Borisionok. He has written for various magazines and publications and curated exhibitions on education and unlearning, workers’ movements and strikes, social movements, and artistic practices in Vilnius, Kyiv, Stockholm, Vienna, and Minsk.

“Rural areas provide for our basic needs, from food to diverse resources and raw materials, which makes rural and urban lives deeply entangled and interdependent. Nevertheless, the voices of people living and working in the countryside are often missing from the public discourse. I am interested in what we can learn from the rural: How can we look beyond cultural stereotypes that tend to regard the countryside as politically backwards and passive and recognize its political potential?” asks curator and dramaturg Katalin Erdődi. Since 2017 Erdődi has been researching rural change through site-specific, collaborative artistic, and curatorial approaches, working across different rural contexts in Hungary, Germany, and Spain.

Kam se poděla hojnost?

Vrací se soběstačné pěstování plodin do života mladých lidí a nebo jde pouze o trend pro hrstku ekologicky smýšlejících nadšenců?

Výstava se zamýšlí nad cenou, již jsme ochotni obětovat k získání kvalitních potravin a zmenšení vlastní stopy, již zanecháváme v životním prostředí. Současně tak ale nečiní naučnou formou v obecné rovině, ale symbolicky na příkladu jedné rozvětvené slovácké rodiny se zemědělskými kořeny.

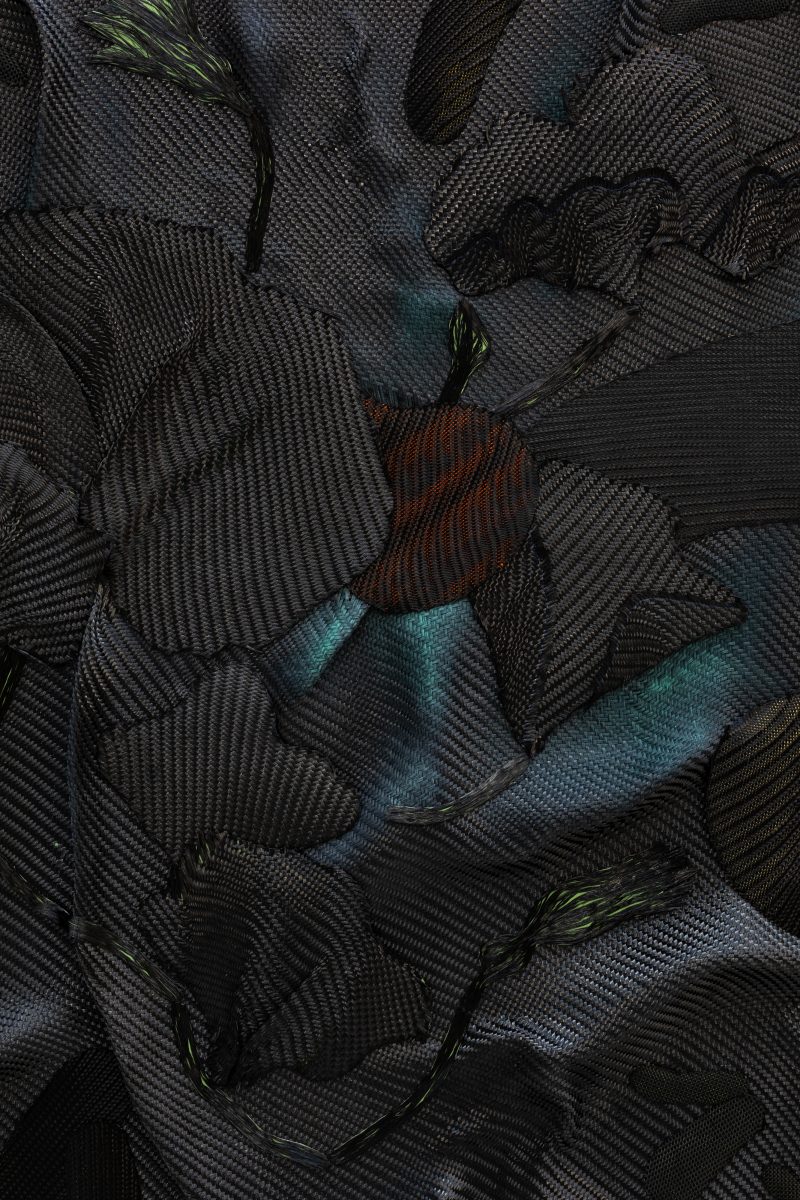

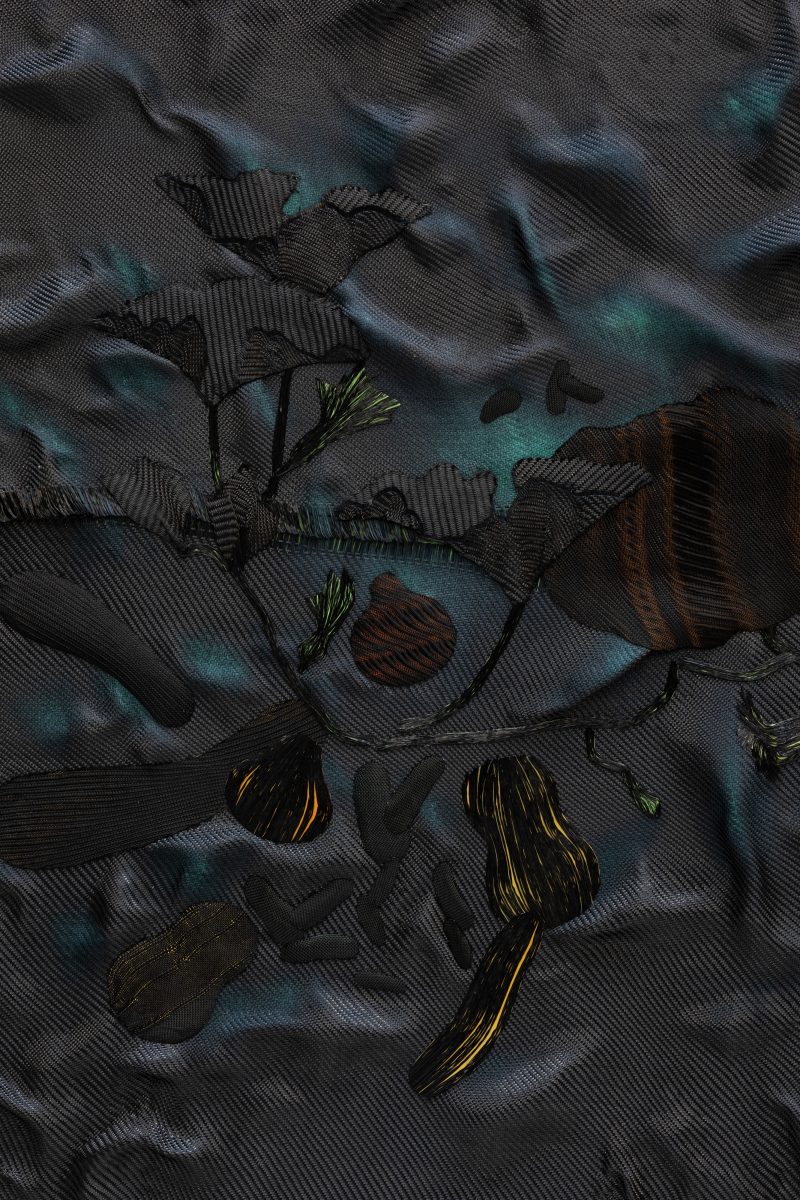

Instalaci obsahuje velkoformátový obraz, na kterém autorka zvěčňuje vlastní portrét a portrét svého manžela, když se ironicky staví do role budovatele v hrdinských pózách, držících v rukou úrodu. Vytváří tak narážku na propagandistické obrazy socialistického realismu, kde světoobčané různých etnik spolupracují v řadě za společným cílem. Druhý velkoformátový obraz z karbonového vlákna ukazuje skutečné zátiší při sklizni plodin z pole.

Natalie Perkof is interested in why more and more young people are turning to farming to produce their own food. Is it just a trend for a few ecologically minded persons, or is it a sign of deeper, more meaningful change? What does abundance – having more than enough of something – mean to us today? Natalie thinks about this through her own experience. She is of Czech-Ghanaian descent, from a South Moravian family with rural roots. A few years ago she started doing organic farming with her family. The concept of plenty has been a popular topic in the history of painting. From Baroque images with the horn of plenty to socialist realist artworks showing abundant harvests as a symbol of good life for all. Today the capitalist system produces plenty for a select few, while the majority faces a global food crisis because of climate change and ongoing wars. This darker side of abundance is also present in Natalie Perkof’s works. In one of her paintings she uses carbon fiber to create a picture of freshly picked crops. There is a tension between the carefully shaped vegetables and the black, oil-like material they are made from. A feeling of unease hangs in the air. Is the harvest in danger? The second canvas shows Natalie and her husband holding crops in their arms. They ironically assume heroic poses as builders of the nation. They remind us of socialist realist imagery that celebrated the alliance of workers and peasants, or the friendship among people.